When the Taliban took over Kabul last month, the team behind Ehtesab, a crowdsourced news alert app (mobile app), left the city. However, they continued to provide crucial information to Afghans, such as whether highways. It was crowded and where violent outbursts had been recorded.

Days later, when two suicide bombers killed more than 70 people near Kabul’s Hamid Karzai Airport as civilians hurriedly rushed to flee, the company used its ground contacts to corroborate the twin strikes within minutes.

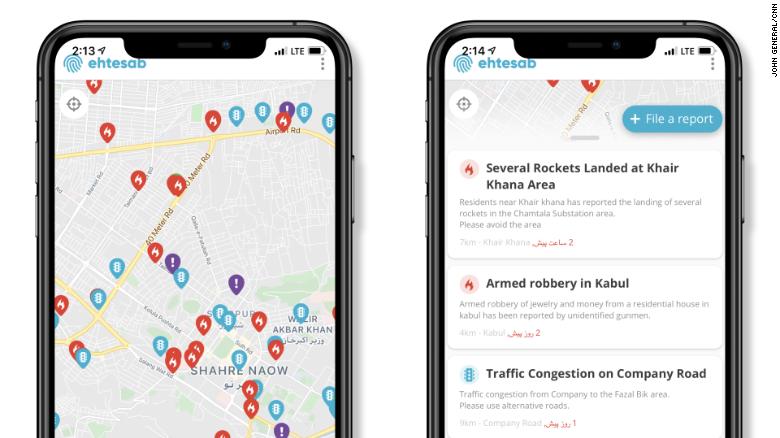

Three years ago, Ehtesab was founded to deliver real-time warnings and information about incidents in Kabul. The purpose was to keep locals involved, overcome communication gaps between citizens and government officials, and hold politicians accountable at the time. Ehtesab, like Citizen, a popular app in the United States for real-time crime warnings, asks residents to report events from throughout the city, from malfunctioning telecommunications to planned demonstrations. Ehtesab’s team of security professionals then verifies these reports.

The fast political and social shift that has followed the Taliban’s takeover has given this program a new sense of urgency. While only 5,000 people in Kabul and elsewhere have downloaded the app — a minuscule fraction of the city’s millions of citizens — the company claims that usage has increased in recent weeks.

Sara Wahedi, the 26-year-old creator of Ehtesab where she holds a degree in human rights and data science from Columbia University, “Its primary focus has been reporting that affects Afghans’ access to food, access to banking and access to the movement.

“In the current environment, we are attempting to alleviate as many difficulties as possible in our normal lives,” she stated. To ensure the safety of my employees is my first problem.”

An app for Kabul locals and those outside the city

Wahedi was born in Afghanistan but was separated from her family when she was six years old. Just as the Taliban’s previous regime was drawing to an end. She traveled to Europe before settling in Canada as an asylum seeker. She spent a year on political science back in 2016 in Kabul where she worked in the office of the former Afghan on social development policies. President Ashraf Ghani for more than a year.

Wahedi caught themselves in the heart of many suicide blasts in Kabul city center in May 2018. She made it home safely, but sanitary issues, power outages, and closed streets plagued her the next day, she claims.

“I was confused by the lack of a platform. Where can you get real-time verifiable information about the events in the city, particularly in a place that constantly plagues by instability,” asked Wahedi. “I was strangely impressed by the fact that there was no structure. Implementing anything like that wouldn’t be prohibitively expensive “opment policy under previous Afghan President Ashraf Ghani’s office

The number of people who could interest in such a service had increased as well. According to the latest available numbers from Afghanistan’s Ministry of Communications and Information Technology, the country has about 10 million internet users and around 23 million cellphone users in 2019, with 89 percent of Afghans having access to telecommunication services.

Before the end of 2018, Ehtesab and her three friends began. After three years, the app now employs roughly 20 individuals in Kabul, including developers, user experience designers, and screening report personnel.

In one of five areas, users may submit reports using the app, such as security, traffic, electricity, corruption, and so on. Users must submit a location, a written description, and a photo or video to utilize the app. The app displays report from at least two sources and update them on a Kabul map as new information is available.

Ehtesab’s prospects

Ehtesab’s work goest more risky and difficult since the Taliban assumed control of Afghanistan. Previously, the app could validate reports using local police records and information from government officials. It now relies more on news reporting, foreign embassies, and the United Nations, which have all reduced their presence in Kabul in recent weeks. The team is also attempting to ensure that the Taliban cannot monitor any reports submitted by users.

Despite the challenges, as well as fears that the Taliban may crackdown on the internet in general, as it did in the early 2000s, Wahedi said the team will not give up.

“The only thing that keeps us going every day is to know that we can do something very directly to help”.’We will continue to do so until we cannot take down the Internet,’ [the crew] stated. [The crew] said. And that’s exactly what we’ve been up to.”

Ehtesab had hoped to operate in at least five additional Afghan cities by December, but Wahedi predicted that the Taliban’s return would push them back until next year. The company is also attempting to determine ways to assist Ehtesab in reaching not only Afghan individuals with smartphones but also those in rural areas with less advanced devices and only 3G connections.

Meanwhile, Wahedi stated that the app may benefit from the assistance of the worldwide IT community, noting that the team is searching for experience in geofencing, location tracking, and satellite services.